From hash houses to diners: a brief history

By B.M. Scott

American diners did not appear fully formed in chrome and neon; they emerged out of 19th‑century hash houses and improvised lunch wagons that fed an industrializing workforce, then evolved into family‑oriented institutions in the 20th century. Tracing that arc—from rough worker cafés to stainless‑steel “homes away from home”—reveals how deeply the diner is welded to ideas of labor, class, and domestic comfort in U.S. culture.

Hash houses in the industrial age (ca. 1870s–1890s)

The term “hash house” was common slang by the late 19th century, attached to cheap eateries that served hashed meats, stews, eggs, and coffee to laborers, boarders, and travelers. These places proliferated in rapidly industrializing cities after the Civil War, as factories, rail yards, and workshops concentrated workers who needed fast, inexpensive calories near their jobs. Hash houses were typically open long hours, located near depots, docks, or industrial districts, and were notorious for indifferent cooking, crowded counters, and a boisterous, all‑male clientele. Their famous “hash house lingo”—comic nicknames for menu items shouted between counter and kitchen—was already noted in newspapers by the 1880s and 1890s, marking them as distinct subcultural spaces within the urban landscape.

Walter Scott and the night lunch wagon (1872 and after)

The move from fixed hash house to mobile diner begins in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1872, when Walter Scott converted a small freight wagon into what he called a “night lunch” wagon. Working outside the Providence Journal offices from dusk to around 4 a.m., Scott sold sandwiches, pies, and coffee to printers and other night workers at a time when conventional restaurants typically closed by 8 p.m. In 1872 he quit his newspaper job entirely and went into the food business full‑time, effectively creating a new niche that addressed the temporal demands of industrial shift work. Scott continued operating until 1917, but by the 1880s and 1890s many imitators had appeared in Eastern cities, transforming the “night lunch” wagon into a recognized urban type.

From wagons to prefabricated “diner cars” (1880s–1930s)

By 1887, Thomas Buckley in Worcester, Massachusetts, was commercially producing lunch wagons, turning Scott’s improvised solution into a manufactured product that could be ordered, shipped, and parked on a street or lot. These wagons gradually grew larger and more elaborate in the 1890s and early 1900s, adding interior counters and stools so customers could eat inside rather than on the curb. As cities restricted street vending and automobile traffic increased in the early 20th century, many operators shifted from fully mobile wagons to semi‑permanent or fixed installations, often set on foundations but still built as narrow “cars.” Manufacturers in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and later New Jersey developed standardized, railcar‑like diner shells—metal‑clad, window‑lined, and optimized for a compact line kitchen—that could be transported by rail or truck and installed almost anywhere.

Industrialization, mobility, and the railroad dining car

The industrial economy that created the need for hash houses and night lunch wagons also supplied the aesthetic vocabulary of the diner. Railroad dining cars, which spread after the 1860s with the expansion of long‑distance rail travel, normalized the idea of eating in a narrow, self‑contained car, served from a compact galley. Prefabricated diners borrowed this form directly, with elongated bodies, rows of windows, and interiors organized as aisles, counters, and booths reminiscent of train car seating. By the 1920s and 1930s, as automobiles and highways reshaped American mobility, these car‑like diners transitioned from urban night trade to roadside fixtures, serving traveling salesmen, truckers, and commuters alongside local workers.

From workers’ cafés to family diners (1930s–1960s)

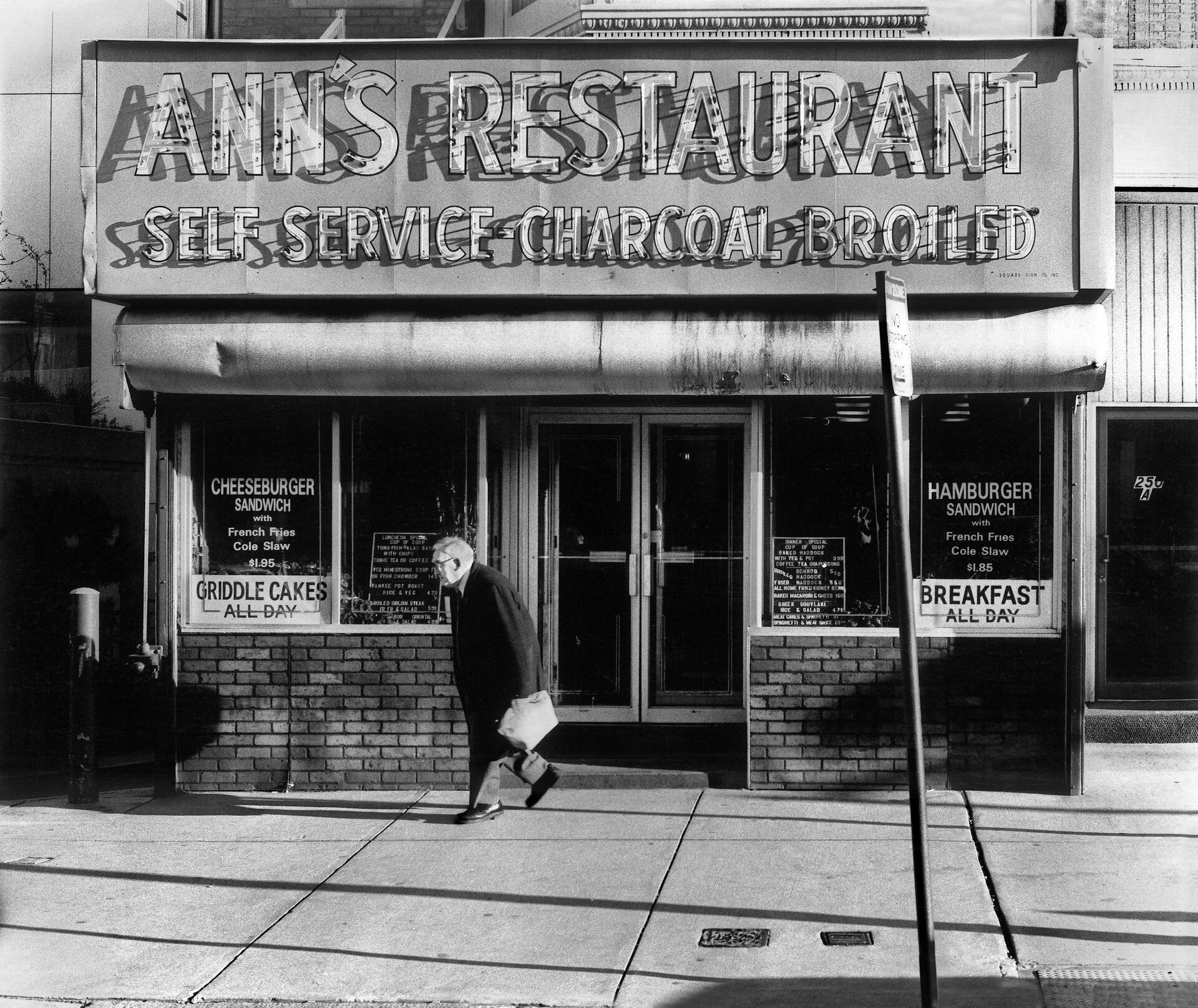

In the interwar years and especially after World War II, the social optics of diners shifted from rough male spaces to more broadly welcoming, often family‑oriented establishments. Manufacturers introduced sleeker stainless‑steel exteriors, neon signage, and more comfortable booth seating, while owners expanded menus beyond basic hash and coffee to include pancakes, club sandwiches, salads, and children’s offerings. Suburbanization after 1945, along with rising car ownership and the emergence of a lower‑middle‑class consumer base, made the diner a convenient, relatively inexpensive alternative to cooking at home, particularly for families on the go. By the 1950s and 1960s, the diner stood alongside the new fast‑food chains as a key institution of American family life, distinguished by table service, extended hours, and a sense of continuity with earlier working‑class café culture.

The diner in American popular imagination

From the 1970s onward, even as the number of independent diners fluctuated, the image of the diner solidified in popular culture as a quintessential American space. Films and television series consistently use diners as democratic stages where workers, families, teenagers, and loners share a counter and a pot of coffee, enacting a vision of America that links industrial labor, mobility, and domestic comfort in a single built form. In this sense, the chrome‑and‑formica diner is the polished heir of the noisy hash house and the smoky night lunch wagon, carrying forward their industrial‑era function—feeding people when and where the work is—while inviting us to imagine that everyone, from shift worker to traveling politician, can sit down together at the same booth.

Questions For Reflection

- How do hash houses and night lunch wagons change the way you imagine everyday life for workers in rapidly industrializing American cities?

- In what ways did industrial schedules—night shifts, factory hours, railroad timetables—shape where, when, and with whom people ate?

- When diners became more family‑oriented in the mid‑20th century, what was gained—and what was lost—from their working‑class origins?

- Think about your own life: do you associate diners more with work (on the clock, commuting, late shifts) or with family and friends (weekend breakfasts, road trips)? Why?

- The diner is often described as a “democratic” space. Does your experience of real diners match that ideal, or reveal exclusions and hierarchies that the myth glosses over?

- How does the evolution from hash house to family diner mirror broader changes in American ideas of home, gender roles, and who is expected to cook?

- As more meals move into chains, delivery apps, and drive‑throughs, what parts of diner culture—if any—feel worth preserving?

- If you were to design a “21st‑century diner” that honestly reflects today’s work patterns and family structures, what would it look and feel like?

Recommended Reading:

Gutman, Richard J. S. American Diner: Then and Now. HarperPerennial, 1993.

Witzel, Michael Karl. The American Diner. MBI Publishing Company, 2006.

Offitzer, Karen. Diners. MetroBooks, 1997.

Cultrera, Larry. Classic Diners of Massachusetts. Arcadia Publishing, 2011.

Haley, Andrew P. Turning the Tables: Restaurants and the Rise of the American Middle Class,

1880–1920. The University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Freedman, Paul. Ten Restaurants That Changed America.

Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2016.

Browne, Rick. A Century of Restaurants: Stories and Recipes from 100 of America’s Most

Historic and Successful Restaurants. Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2013.

Kraig, Bruce. A Rich and Fertile Land: A History of Food in America.

Reaktion Books, 2017.

Shapiro, Laura. Perfection Salad: Women and Cooking at the Turn

of the Century. North Point Press, 1986.

Shapiro, Laura. Something from the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America.